by Dan Gonzalez

In the past 3 articles we have looked at basic tools for drum editing as well as identifying, splitting, cropping, and aligning clips. All of these techniques can be followed pretty accurately by reading along and performing the functions as I’ve written them. This portion of the blog series will require that you listen intently to what you’re doing as we work through it.

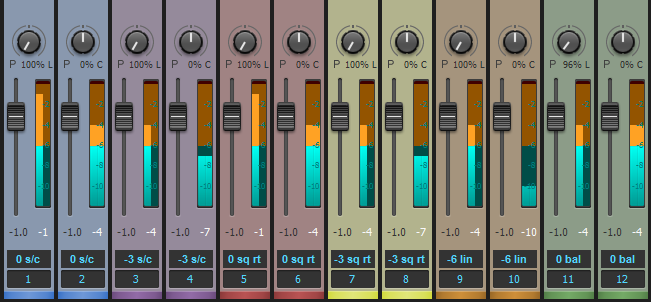

Make sure to wear headphones and get your critical listening ears on so that your drum edits are clean and not full of pops. Previously I mentioned that we would need to monitor our drums as we edit them and that erroneous edits come through the most in the cymbal microphones. In order to make this possible we’re going to mute the tom tracks and lower the volume for the kick and snare tracks. This exposes mostly high hat, ride, and overhead microphone signals. Also, make sure to pan the overhead microphone signals hard left and right too.

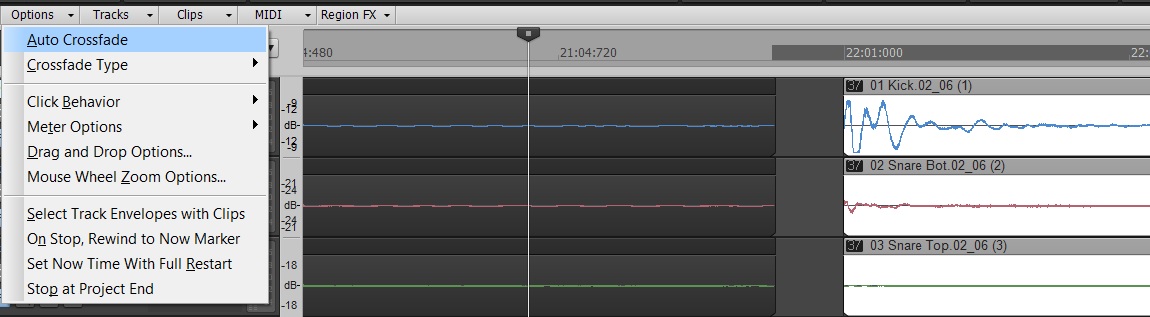

STEP 14: Turn on Auto Crossfade

SONAR is known for it’s streamlined feel and quick functions. One of the best examples of this is SONAR’s auto cross-fade functionality. Since we’re putting this drum pattern back together we’ll need some speedy way of making sure the clips do not pop when overlapping.

Within the track view click on the Options > Auto Crossfade. This feature allows you to crop one clip into another and automatically yield a cross fade. Continue reading “Multi-track Drum Editing – Crossfading and Critical Listening”

Fig. 1: This lowpass filter response has a cutoff of 1100 Hz, and a moderate 24/dB per octave slope.

Fig. 1: This lowpass filter response has a cutoff of 1100 Hz, and a moderate 24/dB per octave slope.

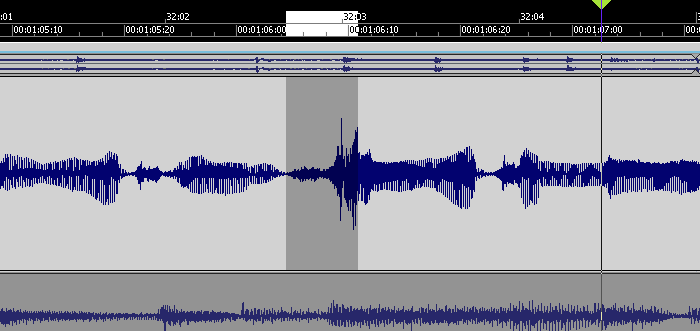

This peak is considerably louder than the rest of the vocal, but reducing it a few dB will bring it into line.

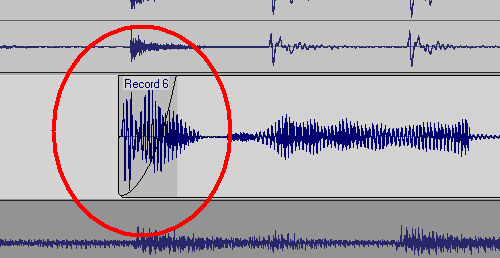

This peak is considerably louder than the rest of the vocal, but reducing it a few dB will bring it into line. The clip on the left has been normalized and faded out. The silence between clips has been cut away. The clip on the right fades in, but has not been normalized.

The clip on the left has been normalized and faded out. The silence between clips has been cut away. The clip on the right fades in, but has not been normalized.

NYC based mixing and recording engineer Liu Ortiz has seen it from all sides of the music and business spectrum. Starting out at such a young age of 16 as an engineer, his career has placed him with a perfect balance (at still a young age) with a ton of knowledge in both the digital and analogue worlds. He has worked on tracks with and for artists such as Mary J. Blige, Pink, Luther Vandross, Christina Aguilera, and even RZA to name a few, and was quite a successful engineer at the Hit Factory in New York City.

NYC based mixing and recording engineer Liu Ortiz has seen it from all sides of the music and business spectrum. Starting out at such a young age of 16 as an engineer, his career has placed him with a perfect balance (at still a young age) with a ton of knowledge in both the digital and analogue worlds. He has worked on tracks with and for artists such as Mary J. Blige, Pink, Luther Vandross, Christina Aguilera, and even RZA to name a few, and was quite a successful engineer at the Hit Factory in New York City. Neve and SSL’s had such distinctive qualities about them similar in comparison to that of Strats and Les Pauls. Since I worked on both extensively, I remember all the little nuances that each series had. So when I am mixing I just try my best to EQ with those particular traits in mind since they were my personal favorites. Pretty much all DAWs now are inherently very neutral, so I can dial in whatever tone I want and don’t have to worry about the vocals or guitars becoming shrill. I really appreciate technology now and just concentrate on crafting the best mix possible. I must add that it is pretty amazing to me that SONAR X3 has a Console Emulator built into every bus and every track – this blew me away

Neve and SSL’s had such distinctive qualities about them similar in comparison to that of Strats and Les Pauls. Since I worked on both extensively, I remember all the little nuances that each series had. So when I am mixing I just try my best to EQ with those particular traits in mind since they were my personal favorites. Pretty much all DAWs now are inherently very neutral, so I can dial in whatever tone I want and don’t have to worry about the vocals or guitars becoming shrill. I really appreciate technology now and just concentrate on crafting the best mix possible. I must add that it is pretty amazing to me that SONAR X3 has a Console Emulator built into every bus and every track – this blew me away