by Craig Parmerlee – SONAR user since SONAR 7

SONAR and other DAWs are used heavily to produce high-quality recordings, while other people use SONAR as part of a compositional process. I find that most of my SONAR usage is a little different, processing live recordings tracked in a concert or club setting. This usage presents various problems that aren’t as apparent in a controlled studio setting. This blog will present a workflow and various SONAR features I have found valuable when processing live recordings.

Objectives

- In most cases, my primary objective is to produce a recording that the musicians can study in order to improve their performance.

- In some cases, the performance and production quality will be high enough to serve as demo material to promote the group.

- I try to deliver a mixed and mastered copy to the musicians within 48 hours, while the event is still fresh in mind, so speed and efficiency are very important.

- Often a musician will ask for a further edit on one of the songs, for example, to include in their personal résumé. Flexibility and ability to recall settings are important.

Changing Expectations

Years ago, I did such projects using Audacity, which seemed adequate at the time. However, expectations have changed radically.

Today many musicians have a low-cost stereo field recorder such as the TASCAM DR-40.These recorders are the equivalent of point-and-shoot cameras. For around $100, they can produce remarkably good quality under ideal circumstances.

This has become the baseline against which many musicians judge other live recordings. Even though I want to produce quick results, if I can’t do substantially better than a TASCAM DR-40, for example, then I am wasting my time (I should note I love those small field recorders and often use them too, but that is not the subject of this blog).

Fortunately, with SONAR I have found a work flow and a set of “go-to” features that allow me to do much better than a stereo field recorder almost every time, using only the microphones that are already placed for the live PA system.

A Word About My Background

I am primarily an instrumentalist (brass player). Musically I perform in and record symphony orchestras, concert bands and jazz groups from small combos to 18-piece big bands.

I have been around recording studios and live PA systems for decades, but never considered myself an expert, and still don’t. I have been a very casual SONAR user since version 7, but have only started to become a serious DAW user in the past 3 years, so I still feel like a neophyte.

I will not be presenting any exotic techniques in this blog. My emphasis is on the overall process, not the processing per se.

The Case Study

The ensemble for this case study is a full-sized “Vegas style” jazz band that presents stage concerts. Specifically this group consists of:

- 5-piece sax section, with doubles on flute, clarinet, and bass clarinet.

- 4-piece trombone section

- 4-piece trumpet section

- Piano, guitar, bass and drums

- Many vocalists, one or two at a time

The material in this concert ranged from quiet ballads to screaming high energy pieces.

The PA system normally uses about 22 mics. On this occasion, requirements of the venue limited us to a 16-channel board. One channel was used for background music and we later discovered one other channel was dead, so we actually recorded on 14 channels.

Challenges of the Live Environment

- Typically, set-up of the PA system and sound check are chaotic; this leaves little time for recording optimization.

- The stage is a noisy area with opportunity for sound to bleed across mics.

- Musicians may not be consistent in their use of mics. In particular, when working with multiple vocalists, the levels can vary widely.

- The microphones are typically below studio grade. If direct boxes are used (e.g. for piano and bass) they may be noisy.

- There is no opportunity to stop the performance and make adjustments for a better recording. And of course, there are no do-overs.

- So, my approach is to do the best to influence the set-up to be useful, and then rely on the power of SONAR to help me overcome any problems that result.

SONAR to the Rescue

Let me quickly dispense with the items that aren’t related to SONAR per se:

- I consult with the sound engineer to come up with mic usage that will be good for both live PA and recording. In our case, we settled on five individual mics for the saxes because most of the solos come from the saxes and the saxes double on distinctly quieter instruments like flutes and clarinets. We used a single overhead and a kick mic for the drums. The guitar amp got a mic. Piano and bass got direct boxes. And there were two vocal mics plus a separate mic and staging area for brass soloists.

- That left only 2 mics to cover the brass. We agreed to float studio booms to both ends of the trombone section to pick up both the trombones and trumpets. One of these floating mics was near the drum kit. We added sound baffles to minimize the drum presence on this mic.

- We used studio-quality mics for the brass, overhead and kick mics together with dependable dynamic mics for the other positions.

The best work flow? It is all about speed

When I first started processing multi-track live performances several years ago, I was concerned that the recording files were huge. Recording at 44.1 kHz and 24 bits, each track is often 1 GB in size or larger.

My ideal configuration was to have the entire program in a single SONAR project so that I could begin by mixing everything as a unit, and later split the program into individual songs. I really expected this would be unwieldy, but that was the dream anyway.

In fact, SONAR is so fast that this configuration is not only possible, it is effortless. In my case, I do move the entire project to a solid state drive, but even running from a hard drive, this is entirely practical.

In the process of mixing, I might use a total of 60 effects for 16 channels. The performance is so good that I never have to give any consideration to freezing tracks. The upshot is that I can fly through the rough mixing stage in a few minutes for the entire concert.

Attack the mud and noise

When it is not possible to have close microphones on every instrument, it is likely that sound bleeding across microphones will create a muddy sound that is difficult to mix, and may even contribute audible artifacts like comb filtering. It is usually worthwhile to go through every track to minimize the non-essential sound. I do this with three techniques:

- High pass and low pass filters narrowing to the desired instruments and their main overtones

- Noise gates in microphones that are not used continuously (i.e. vocal and solo microphones)

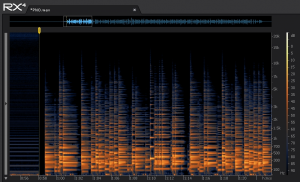

- Noise and hum reduction processing. In this case, I use Izotope RX4. However, in my work flow, I wait until I have a rough mix, then I solo each channel to listen for anything that might call for extra noise reduction. This is typically needed on low-end direct boxes. In addition, there can be situations where the building’s HVAC system adds a constant layer of LF noise to many tracks. My work flow is to exit SONAR and then use RX4 stand-alone directly on the files in SONAR’s Audio folder.

Where’s the kick drum?

On this project, we discovered that the channel for the kick drum was dead. This was extremely disappointing because, although the kick is not dominant in this genre, it ties the rhythm section together. I immediately had a fear that this was going to be a seriously degraded recording.

But wait. Didn’t SONAR Platinum just add Aux Tracks? Maybe this is a good application for that new feature.

But wait. Didn’t SONAR Platinum just add Aux Tracks? Maybe this is a good application for that new feature.

I took the overhead mic and sent it to two aux channels. I used EQ to tailor the first aux channel to cover the cymbals and snare.

As it turned out, the overhead mic got enough of the kick and toms to be useful.

I used EQ to remove the cymbals from the second aux channel and added very narrow filters on the fundamental and first overtone of the bass drum and also allowed some tom in on that aux channel.

While not a classic rock kick sound, it was surprisingly good. It didn’t seem quite punchy enough, so I added a little transient shaping to make the kick “kick”.

At first I thought I might want to try the new drum replacer feature to synthesize the kicks, but the above technique worked so well that I didn’t even try the drum replacer. It is nice to know that is yet another SONAR solution if I need it in the future.

Now, on to a tighter mix

With the various problems solved and the noise minimized, I can do more conventional mix techniques adding compression, reverb, and other normal processing and adjusting stereo placement.

I won’t go into detail, as this is very much like mixing any other project. The main difference is that I am still working on the entire concert as a single unit at this stage.

My goal is to quickly get a mix where all tracks sound good without major adjustments between songs.

The final frontier: Individual song mixes

Remember that one objective is speed. For this project, I was able to do all of the above for a 2-hour concert in about one hour, and the result is a continuous program that sounds pretty good.

The next step is to insert split points and do any special adjustments that might be needed for each song. But that is a dilemma. If I am successful in producing a decent mix, it is very likely that some of the musicians will come back and say “Hey, can I get a new mix of that tune with the tenor solo a little hotter in the mix?” or “Could we try just a little more reverb on Cheri’s song?

In the past, if I really wanted to accommodate these requests, it probably would have been necessary to save each song as a separate SONAR project.

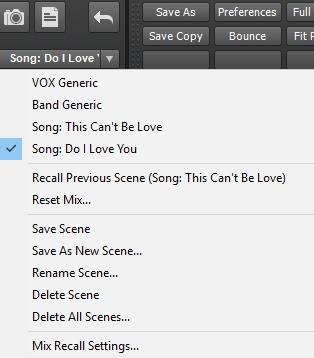

In fact, I have done exactly that many times. That’s a real time killer and adds to disk drive clutter. SONAR’s new Mix Scenes feature changes that in a dramatically powerful way.

With Mix Scenes, I can maintain a single SONAR project for the entire concert. I save a default scene for the instrumentals and a second default scene for songs with vocals, as there are significantly different settings for the vocal songs.

Then if any songs need additional tweaking beyond my defaults, I simply save a scene for that song.

Later, if anybody wants a more refined mix, I can instantly return to the settings I used for that song.

In summary, this combination of SONAR capabilities has allowed me to use a work flow that is very quick from end to end, produces good results quickly, and yet preserves all the flexibility to refine the mixes later.